The practice of sacrificial killing – offering a life to appease, honor, or commune with the divine – spans millennia and continents, threading through the religious histories of humanity. From the Abrahamic traditions of the ancient Near East to the Vedic rituals of South Asia, and across countless indigenous faiths, the act of slaughter has been imbued with spiritual significance, often seen as a transactional gesture to secure favor or purity. In the Indian subcontinent during the lifetime of Sri Guru Nanak Dev Ji, such practices persisted, embedded in both elite and folk traditions. Within Sikhi, however, the practice of Jhatka – particularly as practiced by the Nihang Sikhs and institutionalized at Hazoor Sahib – presents a complex intersection of historical continuity and theological divergence. This essay examines the persistence of sacrificial killings in Sikhi against the backdrop of other religious traditions, interrogating their alignment with the transformative vision of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji.

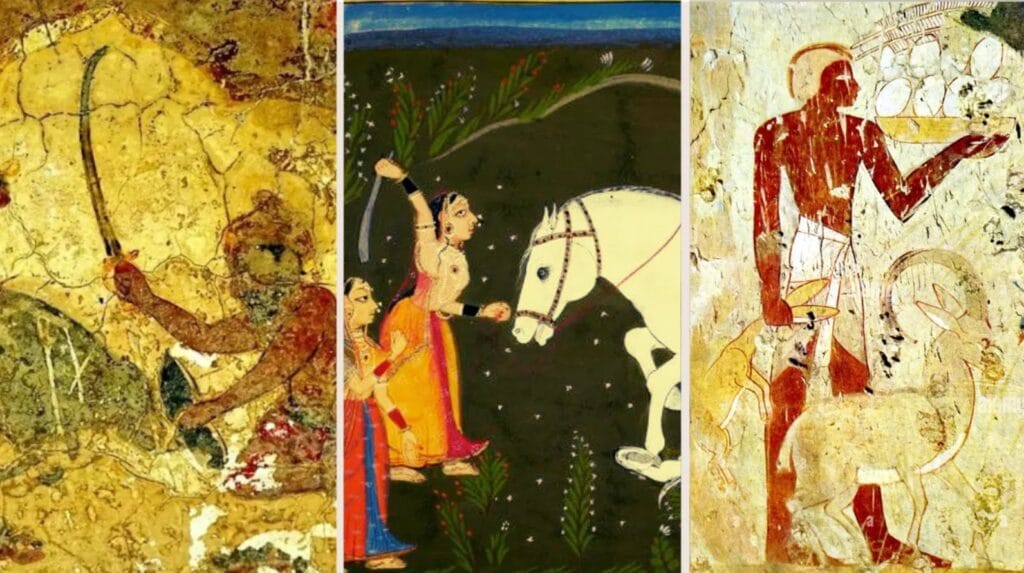

Sacrificial killing is a near-universal phenomenon in premodern religious systems. In the Hebrew tradition, the binding of Isaac and the Passover lamb framed sacrifice as an act of obedience and redemption, a covenantal exchange with a transcendent God. In Vedic Hinduism, the ashvamedha (horse sacrifice) and other rituals offered blood to deities like Agni or Kali, reflecting a cosmology where life-force mediated human-divine relations. Indigenous traditions worldwide similarly tied slaughter to seasonal cycles, warfare, or cosmic order. In 15th-century India, these currents converged: Hindu temple sacrifices to Devi persisted alongside folk practices, even as Jainism and Buddhism advocated non-violence (ahimsa). Guru Nanak Dev Ji entered this landscape not as a participant but as a critic, redefining the very notion of sacrifice.

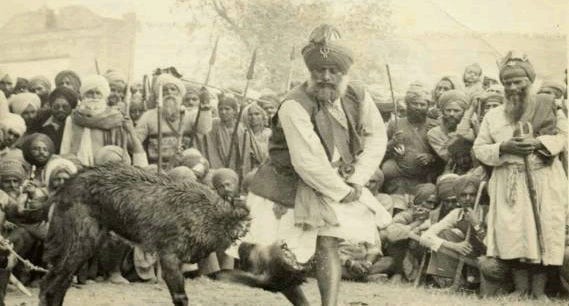

Within the Sikh community, Jhatka emerges as a contested practice. Ostensibly a method of slaughter distinct from the Islamic halal (which involves a slower bleed-out), Jhatka is often defended as an ethical means of meat consumption, minimizing suffering. Yet, its enactment at Hazoor Sahib reveals a ritualistic dimension that transcends mere utility. Here, goats are killed and their meat presented before Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji. Weapons – a physical representation of the Divine – are anointed with the blood, evoking pre-Sikh tribal practices where tools of survival were consecrated through death.

This ritual bears hallmarks of sacrificial killing: an offering to a deity, a symbolic exchange of life for blessing. Nihang groups venerate this maryada as an authentic expression of Sikh tradition, rooted in their historical role as warriors defending the faith. However, its syncretic nature – blending Sikh praxis with Indic ritualism – raises questions about its fidelity to the Gurus’ teachings. The absence of textual justification from Gurbani suggests a practice more indebted to cultural inheritance than Sikh theology.

The Guru Granth Sahib Ji offers a radical critique of external rituals, including sacrificial killing, reorienting the locus of spiritual action from the physical to the internal. Guru Nanak Dev Ji confronts the act of ritualistic animal slaughter directly:

Though addressed to Islamic halal, this critique applies equally to Jhatka as ritual offering. If the Divine permeates all creation, what purpose does killing serve? Jot-Vigaas – the ability to witness Akal Purakh’s divine Light from within – is not enhanced by bloodshed; the act is rendered hollow.

Sri Guru Nanak Dev Ji further questions the dharmic value of such violence:

This piercing inquiry exposes the contradiction: labeling slaughter as dharam inverts the ethical order Gurbani upholds. Killing another to sanctify oneself is not purity – it is adharam, a stain on the soul.

The alternative is internal awakening, as Sri Guru Amar Das Ji teaches:

True sacrifice is the death of haumai, not the slaughter of a sentient being. This inward turn redefines sacrifice as a spiritual act, free of violence.

Finally, Sri Guru Ram Das Ji offers the ultimate offering:

This surrender – to the divine will, not a deity’s altar – encapsulates Sikhi’s vision. Blood is irrelevant; the mind’s submission is the true offering.

This equanimity marks the Sikh ideal of sacrifice: the annihilation of the ego, not the destruction of another life. Gurbani thus stands in direct opposition to the notion that blood purifies or propitiates, asserting instead that it taints both the actor and the act.

Gurbani’s rejection of external killing finds its fullest expression in the Khande-ke-Pahul Amrit ceremony. Here, the Khanda becomes the instrument of true sacrifice. When a Sikh offers their head to the Khanda, it is not a physical death but a profound spiritual act: the killing of the old self, the ego-laden identity, and a rebirth into the Khalsa. This is the sacrifice Gurbani extols – a voluntary surrender to the Guru’s hukam, where the blade severs haumai and the Amrit renews the soul in alignment with Akal Purakh. Unlike the blood of goats at Hazoor Sahib, this sacrifice stains no altar; it transforms the initiate into a living embodiment of the Guru’s teachings.

When juxtaposed with other religious frameworks, Sikhi’s rejection of sacrificial killing as a spiritual mechanism becomes pronounced. Abrahamic traditions often frame sacrifice as a covenantal act – blood as a seal of fidelity or atonement. Hinduism’s sacrificial rites, such as those to Devi, posit a transactional relationship with deities, where life-force balances cosmic debts. Indigenous practices frequently align slaughter with communal survival, embedding it in ecological or martial contexts. In each, the divine is externalized, a recipient of offerings.

The Nihang Jhatka, with its blood offerings and syncretic elements, aligns more closely with these externalized traditions than with the Gurus’ vision. Its persistence reflects a historical synthesis – Sikh martial identity grafted onto pre-Sikh ritualism – rather than a theological imperative.

Why, then, does Jhatka endure within the Sikh community, particularly at Hazoor Sahib? Its roots lie in the Nihangs’ historical context: a community forged out of the political landscape of 17th and 18th-century persecution, where the surviving Sikh population turned to meat for sustenance and survival. The ritualistic overlay – the anointment of blood, the offering of flesh – likely emerged from the cultural milieu of the Deccan, where Hazoor Sahib sits, a region steeped in Hindu devotional practices. This syncretism, while a testament to the community’s malleable tendencies, diverges from the Gurus’ emphasis on Gurbani as the central arbiter of practice.

Notably, Nihang defenses of Jhatka rarely cite Gurbani, relying instead on oral tradition and historical precedent. This omission underscores a disconnect: Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, though physically central at Hazoor Sahib, is seldom invoked to justify the Gurdwara’s distinct maryada. The practice thus occupies a liminal space – cherished as heritage yet unmoored from Sikh scripture.

Sacrificial killings, whether in Sikhi or other faiths, reflect humanity’s ancient impulse to bridge the human-divine divide through violence. Yet, Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji offers a counter-narrative: the only life to be sacrificed is the ego, the only blood to be shed is the illusion of separation. The Jhatka of Hazoor Sahib, with its offerings of blood and its echoes of pre-Sikh ritualism, stands as a historical artifact – an inheritance at odds with the Gurus’ transformative ethic. For Sikhs, the challenge is to honor our past without being bound by it, to elevate Gurbani above tradition when the two diverge. In a dharam where the divine dwells within, the true sacrificial offering is not animals, but the mind’s surrender – a sacrifice that leaves no stain.

Written By: Musäfr

We’re here to help. Whether you’re curious about Gurbani, Sikh history, Rehat Maryada or anything else, ask freely. Your questions will be received with respect and answered with care.

Ask Question