According to the Sikh Rehat Maryada and Sri Akal Takhat Sahib, Raagmala is not Gurbani and not authored by the Sikh Gurus. It appears only in the appendix of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, a section historically used by scribes to include supplementary material. This status is made clear by the directive that the Bhog of a complete Sehaj or Akhand Paath concludes at Mundaavani, while the reading of Raagmala is optional. Gurbani revealed by the Guru can never be optional; a Sikh cannot choose which portions to accept or omit. The very fact that Raagmala may be read or not read demonstrates that it is not Gurbani, but an additional text of historical interest included in the appendix, similar to other non‑canonical materials preserved by scribes. Unfortunately, a lack of accurate information has caused some to view Raagmala as controversial, even though the matter is straightforward when its historical context is correctly understood.

Let’s learn more.

A complete reading of the Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji begins with Sri Japji Sahib, excluding the first eighteen pages, which consist of the title page, table of contents, and index. It is universally accepted by all Sikhs that these eighteen pages are not part of the primary text of Gurbani. However, Sikhs hold a range of perspectives on the appendix added by scribes over time to Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, and its significance. Specifically, there are three main views:

A complete reading of the Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji concludes with the composition titled ‘Mundaavani Mahalla 5,’ excluding the appendix, as it is not considered part of the main text and does not hold the status of Gurbani.

A complete reading of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji includes the appendix, recognizing it as supplementary material added by scribes, though it is not classified as Gurbani.

A complete reading of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji incorporates the appendix, and views it as holding the same status as the main body of the holy text.

There are several writings that have been included as appendices in various handwritten copies of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji over time. The most common of these in historical handwritten copies is ‘Siaahi Ki Bidhi’, which translates to ‘the technique of how to prepare the ink.’ It was a common practice for scribes to describe the ink preparation method. The reason for this was quite practical: if an ang (holy page) of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji became damaged or worn out and needed to be repaired or replaced, the spare blank pages bound at the end of the appendix were used to rewrite the specific ang.

Other compositions, found in the appendices of some handwritten copies of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, follow ‘Siaahi Ki Bidhi’ and include:

Hakikat Raah Mukaam Raaje Shivnabh Ki: An anonymous, undated Punjabi prose piece not recognized as Gurbani. Found in some manuscript copies, particularly the one attributed to Bhai Banno, it always appears after Mundaavani and before Raagmala. It describes a travel guide to Sangladip (Sri Lanka) rather than a firsthand account. It is universally rejected as Gurbani and regarded as an appendix added by a scribe.

Praan Sangli: Another anonymous, undated Punjabi prose piece not recognized as Gurbani, also found in the Beerh, attributed to Bhai Banno. It appears after Mundaavani and before Raagmala. The title means “Chain of Vital Breath” and interprets Hatha Yoga, purportedly taught to Raja Shivnabh of Sangladip. It is universally rejected as Gurbani and regarded as an appendix added by a scribe.

Rattan Mala: A spiritual composition appended in some manuscript copies, particularly the one attributed to Bhai Banno. Titled “Raag Raamkalee Rattan Mala Mahalla 1,” some versions omit “Mahalla 1.” It explores spiritual devotion and Hatha Yoga. It is universally rejected as Gurbani and regarded as an appendix added by a scribe.

Jit Dar Lakh Muhammada: An anonymous, undated Punjabi prose piece, appearing after Mundaavani and before Raagmala. It lists prophets and deities, concluding that none attained peace without the True Guru’s teachings. Though its content aligns with Sikh teachings, it was universally rejected as Gurbani and is regarded as a scribe’s addition.

Raagmala: A composition appended to many manuscript copies, either at the time of compilation or later by scribes. Always appearing after Mundaavani and any other appended texts, it is included in all SGPC-printed versions. ‘Raagmala,’ meaning “garland of raags,” lists musical frameworks differing across sources. The version in Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji has 12 verses (60 lines), aligning with the Hanuman school of Indian music but not fully matching the raags used in the scripture. It also appears in the poetic novel Madhav Nal Kaam Kandlaa (stanzas 34–38 of 179).

The “Raagmala” composition is derived from poet Alam’s “Madhav Nal Kaam Kandla,” a love story interwoven with a love for traditional classical music. Alam, a Muslim writer, describes the musical pieces performed by Pandit Madhav Nal (a music master) for Kaam Kandlaa (a dancer) in stanzas 34-38, which later became known as the separate work “Raagmala,” literally “A list of Raags.”

The “Raagmala” composition is derived from poet Alam’s “Madhav Nal Kaam Kandla,” a love story interwoven with a love for traditional classical music. Alam, a Muslim writer, describes the musical pieces performed by Pandit Madhav Nal (a music master) for Kaam Kandlaa (a dancer) in stanzas 34-38, which later became known as the separate work “Raagmala,” literally “A list of Raags.”

The Aad Granth Ji (this first cannon of scripture), also known as Kartarpuri Beerh, compiled by Fifth Nanak in 1604, does not contain the worldly compositions of Rattan Mala, Hakikat Raah Mukaam, Shiv Naabh Ki Bidhi, or Raagmala in its appendix. It also did not include the Gurbani revealed through Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji, as expected. To ensure its preservation without the possibility of corruption or alteration, a locking system was put in place, and all the prominent Sikhs of the time were made to memorize and internalize the Gurbani, safeguarding the purity and authenticity of the Divine message for generations to come.

The Aad Granth Ji (this first cannon of scripture), also known as Kartarpuri Beerh, compiled by Fifth Nanak in 1604, does not contain the worldly compositions of Rattan Mala, Hakikat Raah Mukaam, Shiv Naabh Ki Bidhi, or Raagmala in its appendix. It also did not include the Gurbani revealed through Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji, as expected. To ensure its preservation without the possibility of corruption or alteration, a locking system was put in place, and all the prominent Sikhs of the time were made to memorize and internalize the Gurbani, safeguarding the purity and authenticity of the Divine message for generations to come.

Also known as the Damdami Beerh, the completed revelation of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji includes the Gurbani of the Ninth Guru, and does not contain Rattan Mala, Hakikat Raah Mukaam, Shiv Naabh Ki Bidhi or Raagmala in its appendix. Guru Sahib included the Gurbani revealed by Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji but did not break the seal of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, which is the “Mundaavani Mahalla 5.” The Gurbani revealed by Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji was added before this seal.

Also known as the Damdami Beerh, the completed revelation of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji includes the Gurbani of the Ninth Guru, and does not contain Rattan Mala, Hakikat Raah Mukaam, Shiv Naabh Ki Bidhi or Raagmala in its appendix. Guru Sahib included the Gurbani revealed by Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji but did not break the seal of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, which is the “Mundaavani Mahalla 5.” The Gurbani revealed by Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji was added before this seal.

In Nanded, Maharashtra, Guru Gobind Singh Ji entrusted the gur-gaddi (throne of guruship) to the fully revealed Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, known as the Damdami Beerh. Carefully compiled, meticulously checked, and divinely approved, this sacred scripture was established as the undisputed eternal Guru, the home of the Divine Creator’s Voice (shabad) & Divine Light (jyot).

In Nanded, Maharashtra, Guru Gobind Singh Ji entrusted the gur-gaddi (throne of guruship) to the fully revealed Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, known as the Damdami Beerh. Carefully compiled, meticulously checked, and divinely approved, this sacred scripture was established as the undisputed eternal Guru, the home of the Divine Creator’s Voice (shabad) & Divine Light (jyot).

The Bhagat Ratnavali, also known as Sikhaa di Baghat Mala, a historic text attributed to Shaheed Bhai Mani Singh Ji, records that some Sikhs approached him with concerns about false interpolations in Janam Sakhis by mischievous writers trying to undermine Sikhi. Fearing similar fabrications in an appendix to Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, they sought guidance. Bhai Mani Singh Ji affirmed that the Bhog (completion) of this Divine Gosht (Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji) is marked by Mundaavani (“The Final Seal”), ensuring any subsequent additions remain unauthorized and not Gurbani. The text states (pages 269-70):

The Bhagat Ratnavali, also known as Sikhaa di Baghat Mala, a historic text attributed to Shaheed Bhai Mani Singh Ji, records that some Sikhs approached him with concerns about false interpolations in Janam Sakhis by mischievous writers trying to undermine Sikhi. Fearing similar fabrications in an appendix to Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, they sought guidance. Bhai Mani Singh Ji affirmed that the Bhog (completion) of this Divine Gosht (Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji) is marked by Mundaavani (“The Final Seal”), ensuring any subsequent additions remain unauthorized and not Gurbani. The text states (pages 269-70):

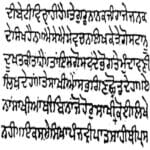

“…ਸਿੱਖਾਂ ਨੇ ਅਰਦਾਸ ਕੀਤੀ ਜੋ ਗੋਸ਼ਟਾਂ (ਗੁਰਬਾਣੀ) ਅੱਗੇ ਹੋਈਆਂ ਹੈਨਿ ਸੋ ਮੇਲ ਵਾਲੀਆਂ ਗੋਸ਼ਟਾਂ ਵਿੱਚ ਆਪਣੀ ਮਤ ਦੀਆਂ ਬਾਤਾਂ ਲਿਖ ਛੋਡੀਆਂ ਹੈਨ … ਐਸੇ ਐਸੇ ਵਚਨ ਲਿਖਕੇ’ ਗੋਸ਼ਟਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਦੂਖਨ ਕੀਤਾ ਹੈ। ਤਾਂ ਇਸ ਗੋਸ਼ਟ ਦੇ ਭੋਗ ਤੇ ਮੁੰਦਾਵਣੀ ਲਿਖਦੇ ਹਾਂ। ਤੇ ਸਾਖੀਆਂ ਸਭ ਗਿਣ ਛੋਡਦੇ ਹਾਂ। ਏਨਾਂ ਸਾਖੀਆਂ ਥੀ ਬਿਨਾਂ ਜੋ ਹੋਰੁ ਸਾਖੀ ਵਿੱਚ ਕੋਈ ਲਿਖੇ ਨਹੀਂ”

Bhai Bhagat Singh, a student of Bhai Mani Singh, is believed to have authored the original Gurbilas Patshahi 6. Reiterating Bhai Mani Singh’s statement on Mundaavani recorded in Bhagat Ratnavali, Gurbilas Patshahi 6 similarly states that Guru Arjan Dev Ji completed the Bhog (completion) of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji at Mundaavani: ਵਾਰ ਵਧੀਕ ਸਲੋਕ ਲਿਖ, ਮੁੰਦਾਵਣੀ ਔਰ ਲਿਖਾਇ ॥ ਤਤਕਰਾ ਲਿਖ ਸਤ ਗੁੰਬ ਕਾ, ਭੋਗ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ ਜੀ ਪਾਇ ॥ (“After writing ‘Salok Vaar Te Vadeek,’ the Granth Ji was concluded with ‘Mundaavani’ and the Index was written.”) However, the author later notes that Sikhs began to read appended compositions, and in blind devotion, some started doing Bhog at Raagmala: ਰਾਗਮਾਲਾ ਪੜ ਪ੍ਰੇਮ ਸੇ ਭੋਗ ਜਪੁਜੀ ਤੇ ਪਾਏ। (“Reading the appended Raagmala with love, they did ‘Bhog’ at Japji Sahib.”)

Bhai Bhagat Singh, a student of Bhai Mani Singh, is believed to have authored the original Gurbilas Patshahi 6. Reiterating Bhai Mani Singh’s statement on Mundaavani recorded in Bhagat Ratnavali, Gurbilas Patshahi 6 similarly states that Guru Arjan Dev Ji completed the Bhog (completion) of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji at Mundaavani: ਵਾਰ ਵਧੀਕ ਸਲੋਕ ਲਿਖ, ਮੁੰਦਾਵਣੀ ਔਰ ਲਿਖਾਇ ॥ ਤਤਕਰਾ ਲਿਖ ਸਤ ਗੁੰਬ ਕਾ, ਭੋਗ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ ਜੀ ਪਾਇ ॥ (“After writing ‘Salok Vaar Te Vadeek,’ the Granth Ji was concluded with ‘Mundaavani’ and the Index was written.”) However, the author later notes that Sikhs began to read appended compositions, and in blind devotion, some started doing Bhog at Raagmala: ਰਾਗਮਾਲਾ ਪੜ ਪ੍ਰੇਮ ਸੇ ਭੋਗ ਜਪੁਜੀ ਤੇ ਪਾਏ। (“Reading the appended Raagmala with love, they did ‘Bhog’ at Japji Sahib.”)

Note: In 2010, the SGPC and the Akal Takhat acknowledged Gurbilas Patshahi 6 as controversial due to its inclusion of elements that disrespect the Sikh Gurus and Sikh teachings, highlighting clear evidence of historical adulteration. However, the republished edited texts were not banned, as it was still considered a historical source, albeit one that must be read with discretion. Only content that fully aligns with Gurbani and does not contradict undisputed historical Sikh texts is acceptable to Sikhs.

Bhai Santokh Singh, also known as Kavi Santokh Singh, a student of the respected Nirmala scholar and then Head Granthi of Sri Darbar Sahib, Amritsar, Giani Sant Singh Ji, clarifies the authorship of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji and Raagmala in his historic work Sri Gur Prataap Suraj Granth (p. 430-431). Aware that some Sikhs had begun reciting appended compositions as part of the Bhog (completion) of the full reading of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, Bhai Santokh Singh asserts that Guru Arjan Dev Ji completed the Bhog up to the final seal of Mundavani:

ਰਾਗਮਾਲ ਸ਼੍ਰੀ ਗੁਰ ਕੀ ਕ੍ਰਿਤ ਨਿਹਂ, ਹੈ ਮੁੰਦਾਵਣੀ ਲਗਿ ਗੁਰ ਬੈਨ । ਇਸ ਮਹਿਂ ਨਿਹਂ ਸੰਸੈ ਕੁਛ ਕਰੀਅਹਿ, ਜੇ ਸੰਸੈ ਅਵਿਲੋਕਹੁ ਨੈਨ । ਮਾਧਵ ਨਲ ਆਲਮ ਕਿਵ ਕੀਨਸਿ, ਤਿਸ ਮਹਿਂ ਨ੍ਰਿਤਕਾਰੀ ਕਹਿ ਤੈਨ । ਰਾਗ ਰਾਗਨੀ ਨਾਮ ਗਿਨੇ ਤਿਹਂ, ਯਾਂ ਤੇ ਸ਼੍ਰੀ ਅਰਜਨ ਕ੍ਰਿਤ ਹੈ ਨ ॥੪੦॥

“Only up to Mundavani is Gurbani; Raagmala is not the work of Guru Sahib. There is no doubt in this, for doubt is dispelled with clear vision. Raagmala is the dance chapter from the novel Madhav Nal written by poet Alam, listing musical measures (Raags and Raagnis). Therefore, it is not the divine word of Guru Arjan Ji.” ||40||

In 1853, during the month of Kattak (mid-October to mid-November), a historic Panthic gathering was convened by Nirmala scholar, Pandit Sobha Singh Dilwali, at the Dera of Sant Dyal Singh in Amritsar. The primary agenda of this significant meeting was to deliberate on preserving and propagating Sikh principles, particularly in the wake of British colonial rule following the fall of the Sikh Empire. The gathering aimed to address the growing influence of external forces and safeguard Sikh traditions and values. During this meeting, it was unanimously concluded that the Raagmala, appended to some manuscripts of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, is not part of Gurbani.

In 1853, during the month of Kattak (mid-October to mid-November), a historic Panthic gathering was convened by Nirmala scholar, Pandit Sobha Singh Dilwali, at the Dera of Sant Dyal Singh in Amritsar. The primary agenda of this significant meeting was to deliberate on preserving and propagating Sikh principles, particularly in the wake of British colonial rule following the fall of the Sikh Empire. The gathering aimed to address the growing influence of external forces and safeguard Sikh traditions and values. During this meeting, it was unanimously concluded that the Raagmala, appended to some manuscripts of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, is not part of Gurbani.

Giani Gian Singh publishes his historic work ‘Tvaareekh Guru Khalsa,” in which he writes (page 419):

Giani Gian Singh publishes his historic work ‘Tvaareekh Guru Khalsa,” in which he writes (page 419):

“ਸਾਰੀ ਬਾਣੀ ਲਿਖਾ ਕੇ ਗੁਰੂ ਜੀ ਨੇ ਅੰਤ ਨੂੰ ‘ਮੁੰਦਾਵਣੀ’ ਉੱਤੇ ਭੋਗ ਪਾ ਦਿੱਤਾ, ਕਿਉਕਿ ‘ਮੁੰਦਾਵਣੀ’ ਨਾਮ ਮੁੰਦ ਦੇਣ ਦਾ ਹੈ, ਜਿਸ ਤਰ੍ਹਾਂ ਕਿਸੇ ਚਿੱਠੀ ਪੱਤਰ ਨੂੰ ਲਿਖਕੇ ਅੰਤ ਵਿੱਚ ਮੋਹਰ ਲਾ ਕੇ ਮੁੰਦ ਦੇਈਦਾ ਹੈ ਕਿ ਏਦੂੰ ਅੱਗੇ ਹੋਰ ਕੁਝ ਨਹੀ…”

“After recording all the ‘Bani’ (revealed Word), Guru Ji concluded the holy text with ‘Mundaavani,’ which means ‘seal.’ Just as a letter is sealed with a stamp after being written, similarly, nothing can be added after ‘Mundaavani.’”

In 1901, under the presidency of famous Sikh saint, Sant Attar Singh Ji of Mastuana, the ‘Panch Khalsa Diwan’ officially declared that Raagmala was not part of the appendix of the original Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji. This decision was part of their broader effort to maintain the integrity and purity of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, rejecting any later appendixes added by later scribes to be deemed Gurbani or necessary to be re-written in Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji. The Diwan’s stance on the appended Raagmala was publicly reiterated.

In 1901, under the presidency of famous Sikh saint, Sant Attar Singh Ji of Mastuana, the ‘Panch Khalsa Diwan’ officially declared that Raagmala was not part of the appendix of the original Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji. This decision was part of their broader effort to maintain the integrity and purity of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, rejecting any later appendixes added by later scribes to be deemed Gurbani or necessary to be re-written in Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji. The Diwan’s stance on the appended Raagmala was publicly reiterated.

Max Arthur Macauliffe, a British scholar and retired judge, spent 25 years studying Sikhi with Giani Partap Singh (1855–1920), leading him to identify with the Sikh faith. In his 1909 work, “The Sikh Religion,” he attributes Raagmala to poet Alam and affirms that Gurbani concludes at Mundaavani by Guru Arjan Dev Ji’s divine order.

Max Arthur Macauliffe, a British scholar and retired judge, spent 25 years studying Sikhi with Giani Partap Singh (1855–1920), leading him to identify with the Sikh faith. In his 1909 work, “The Sikh Religion,” he attributes Raagmala to poet Alam and affirms that Gurbani concludes at Mundaavani by Guru Arjan Dev Ji’s divine order.

Prominent Sikh scholar, Bhai Kahn Singh Ji of Nabha, conducted extensive research on the Kartarpuri Beerh and other Beerhs, concluding that Raagmala was not authored by the Sikh Gurus, nor is it part of the main body of the holy text; therefore, it is not considered Gurbani.

Prominent Sikh scholar, Bhai Kahn Singh Ji of Nabha, conducted extensive research on the Kartarpuri Beerh and other Beerhs, concluding that Raagmala was not authored by the Sikh Gurus, nor is it part of the main body of the holy text; therefore, it is not considered Gurbani.

The Singhs decided to seek the assistance of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji and placed two chits in front of Guru Sahib. The chit stating ‘Raagmala is not Gurbani’ was chosen by Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji as a response that its inclusion in Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji is not necessary nor important.

The first edition of the ‘Sikh Rehat Maryada’ document was published on 12th October 1936, during the SGPC presidency of Bhai Pratap Singh Shankar. The Rehat Maryada document stated that the Bhog or completion of the reading of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji should be done at Mundaavani. Therefore, clearing that the complete Gurbani of Sri Guru Granth Sahib is from “Ik Oankaar” to “Tan Man Theevai Hariaa” (i.e. Mundaavani), and that the appended Raagmala is not Gurbani, and therefore should be not read alongside the reading of Gurbani during an Akhand Paath or Sehaj Paath.

The first edition of the ‘Sikh Rehat Maryada’ document was published on 12th October 1936, during the SGPC presidency of Bhai Pratap Singh Shankar. The Rehat Maryada document stated that the Bhog or completion of the reading of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji should be done at Mundaavani. Therefore, clearing that the complete Gurbani of Sri Guru Granth Sahib is from “Ik Oankaar” to “Tan Man Theevai Hariaa” (i.e. Mundaavani), and that the appended Raagmala is not Gurbani, and therefore should be not read alongside the reading of Gurbani during an Akhand Paath or Sehaj Paath.

SGPC conducted research on Kartarpuri Beerh and concluded that it is not authentic.

The SGPC committee, led by President SGPC and Akal Takhat Jathedar Giani Mohan Singh Nagoke, concluded that the appended Raagmala is not Gurbani and is neither important nor necessary to read. Complete readings of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji at Akal Takhat Sahib continued to conclude at Mundaavani. However, some Sikh shrines, less inclined to follow Akal Takhat Sahib’s ruling, disregarded its decision and that of the SGPC. To unify Sikhs with differing practices under Akal Takhat Sahib and one Panth, the optional reading of the appended Raagmala was permitted as a localized or personal choice.

The SGPC committee, led by President SGPC and Akal Takhat Jathedar Giani Mohan Singh Nagoke, concluded that the appended Raagmala is not Gurbani and is neither important nor necessary to read. Complete readings of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji at Akal Takhat Sahib continued to conclude at Mundaavani. However, some Sikh shrines, less inclined to follow Akal Takhat Sahib’s ruling, disregarded its decision and that of the SGPC. To unify Sikhs with differing practices under Akal Takhat Sahib and one Panth, the optional reading of the appended Raagmala was permitted as a localized or personal choice.

Giani Lal Singh was sent by the SGPC to confirm with Giani Gurbachan Singh Ji Bhindranwale whether he accepted Akal Takhat Sahib’s ruling regarding the Bhog at Mundaavani, while also permitting Bhog at the appended Raagmala where it was the local practice. Giani Lal Singh provided a letter stating that the seminary (taksaal) led by Giani Gurbachan Singh Ji accepted Akal Takhat Sahib’s decree, allowing the reading of the appendix at the conclusion of scriptural recitations as an option.

Giani Lal Singh was sent by the SGPC to confirm with Giani Gurbachan Singh Ji Bhindranwale whether he accepted Akal Takhat Sahib’s ruling regarding the Bhog at Mundaavani, while also permitting Bhog at the appended Raagmala where it was the local practice. Giani Lal Singh provided a letter stating that the seminary (taksaal) led by Giani Gurbachan Singh Ji accepted Akal Takhat Sahib’s decree, allowing the reading of the appendix at the conclusion of scriptural recitations as an option.

The revised version declared that it allows the optional reading of the appended Raagmala for the sake of Panthic unity.

Swami Harnam Das Udaaseen formally known as Nihang Nurang Singh studied various Puratan saroops (old handwritten volumes) of the Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji and concluded that Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji concludes at Mundavani and that the appendix of Raagmala is neither important nor necessary as it is not Gurbani, nor scribed in every handwritten historic manuscript of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji.

Swami Harnam Das Udaaseen formally known as Nihang Nurang Singh studied various Puratan saroops (old handwritten volumes) of the Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji and concluded that Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji concludes at Mundavani and that the appendix of Raagmala is neither important nor necessary as it is not Gurbani, nor scribed in every handwritten historic manuscript of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji.

Pandit Kartar Singh Dakha (1888–1958), a renowned Nirmala scholar and student of Pandit Basant Singh of Thikrivala, published “Raagmala Nirne” in 1969 to demonstrate that the appended Raagmala is not Gurbani and was not part of the appendix of the original Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji.

Pandit Kartar Singh Dakha (1888–1958), a renowned Nirmala scholar and student of Pandit Basant Singh of Thikrivala, published “Raagmala Nirne” in 1969 to demonstrate that the appended Raagmala is not Gurbani and was not part of the appendix of the original Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji.

On 4th September 1970, the Shiromani Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee responded to queries regarding the appended Raagmala, after consulting with the Jathedar of Akal Takhat Sahib and the Singh Sahibs of Sri Darbar Sahib. The response clarified that Akal Takhat Sahib does not permit the recitation of the appended Raagmala, as it is not considered Gurbani. It was noted that Raagmala has no authorship within the text and appears only after the Guru’s seal of Mundaavani and signature in the Beerh held at Kartarpur Sahib.

On 4th September 1970, the Shiromani Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee responded to queries regarding the appended Raagmala, after consulting with the Jathedar of Akal Takhat Sahib and the Singh Sahibs of Sri Darbar Sahib. The response clarified that Akal Takhat Sahib does not permit the recitation of the appended Raagmala, as it is not considered Gurbani. It was noted that Raagmala has no authorship within the text and appears only after the Guru’s seal of Mundaavani and signature in the Beerh held at Kartarpur Sahib.

Although he took control, the Maryada of Akal Takhat remained unchanged. All Akhand Paaths and Sehaj Paaths continued to conclude at Mundaavani, with no appendix texts, like Raagmala, being read. On one occasion, Sant Ji’s nephew, Swaran Singh Rhode, forcefully had Raagmala read at Sri Akal Takhat Sahib. In response to this, Sant Jarnail Singh physically punished his nephew and scolded him and was told that the Maryada or practice of their seminary school remains in the seminary school, and the Maryada or practice of the Panth or collective community remains at Akal Takhat Sahib and all other Sikh shrines.

Although he took control, the Maryada of Akal Takhat remained unchanged. All Akhand Paaths and Sehaj Paaths continued to conclude at Mundaavani, with no appendix texts, like Raagmala, being read. On one occasion, Sant Ji’s nephew, Swaran Singh Rhode, forcefully had Raagmala read at Sri Akal Takhat Sahib. In response to this, Sant Jarnail Singh physically punished his nephew and scolded him and was told that the Maryada or practice of their seminary school remains in the seminary school, and the Maryada or practice of the Panth or collective community remains at Akal Takhat Sahib and all other Sikh shrines.

In June 1984, when the Indian Army invaded Amritsar and carried out what is considered the third holocaust in Sikh history, not only was there significant structural damage and a massacre of Sikhs but Sikh history itself was also targeted. The Sikh Reference Library was ransacked, looted, and set ablaze. Among the losses, the Damdami Beerh, believed to have been handwritten by Guru Gobind Singh Ji and not containing the appended Raagmala, went missing after the library was ransacked. This is documented by Dr. Mohinder Dhillon in his book “Blue Star Ghalughara” (1991).

In June 1984, when the Indian Army invaded Amritsar and carried out what is considered the third holocaust in Sikh history, not only was there significant structural damage and a massacre of Sikhs but Sikh history itself was also targeted. The Sikh Reference Library was ransacked, looted, and set ablaze. Among the losses, the Damdami Beerh, believed to have been handwritten by Guru Gobind Singh Ji and not containing the appended Raagmala, went missing after the library was ransacked. This is documented by Dr. Mohinder Dhillon in his book “Blue Star Ghalughara” (1991).

In January 1986, Bhai Jasbir Singh Rode was appointed Jathedar of Akal Takht. He was the nephew of Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale. However, unlike his uncle, Sant Jarnail Singh, Bhai Jasbir Singh Rode unconstitutionally replaced the Panth-approved Maryada of Akal Takhat with that of the Jatha Bhindran, the seminary to which he belonged. This included mandating the conclusion of all scriptural readings of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji held Akal Takhat Sahib with the appended Raagmala instead of Mundaavani.

In January 1986, Bhai Jasbir Singh Rode was appointed Jathedar of Akal Takht. He was the nephew of Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale. However, unlike his uncle, Sant Jarnail Singh, Bhai Jasbir Singh Rode unconstitutionally replaced the Panth-approved Maryada of Akal Takhat with that of the Jatha Bhindran, the seminary to which he belonged. This included mandating the conclusion of all scriptural readings of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji held Akal Takhat Sahib with the appended Raagmala instead of Mundaavani.

On August 19, 2010, Iqbal Singh, the appointed Jathedar of Takhat Sri Patna Sahib, issued a public edict criticizing Sikhs and Gurdwaras that omit the appended Raagmala from the complete scriptural reading, arguing that it should be included as part of the main body of the holy text.

On August 19, 2010, Iqbal Singh, the appointed Jathedar of Takhat Sri Patna Sahib, issued a public edict criticizing Sikhs and Gurdwaras that omit the appended Raagmala from the complete scriptural reading, arguing that it should be included as part of the main body of the holy text.

On 23rd August 2010, Akal Takht Sahib asserted that only it had the authority to issue hukam-namas (edicts) on community matters, stating that regional takhats could only address local issues. Akal Takhat Sahib urged Sikhs worldwide to continue following the historic practice of scriptural readings and not engage in raking unnecessary issues.

On 23rd August 2010, Akal Takht Sahib asserted that only it had the authority to issue hukam-namas (edicts) on community matters, stating that regional takhats could only address local issues. Akal Takhat Sahib urged Sikhs worldwide to continue following the historic practice of scriptural readings and not engage in raking unnecessary issues.

On 12th November 2015, the Sarbat Khalsa — a gathering of the entire Khalsa — appointed Bhai Jagtar Singh Hawara as the leader of the Sikh nation. Following his appointment, Jathedar Hawara urged the Sikh community to avoid distractions over minor issues at a time when the Sikh nation is facing State oppression and attacks from anti-Sikh forces of all kinds. Discussions about the compositions in the appendix of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji and their status are not of critical importance when Sikhs are fighting for their nation’s survival against oppression, especially when the main body of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, containing the unchanging and universally revered Gurbani, remains uncontested.

On 12th November 2015, the Sarbat Khalsa — a gathering of the entire Khalsa — appointed Bhai Jagtar Singh Hawara as the leader of the Sikh nation. Following his appointment, Jathedar Hawara urged the Sikh community to avoid distractions over minor issues at a time when the Sikh nation is facing State oppression and attacks from anti-Sikh forces of all kinds. Discussions about the compositions in the appendix of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji and their status are not of critical importance when Sikhs are fighting for their nation’s survival against oppression, especially when the main body of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, containing the unchanging and universally revered Gurbani, remains uncontested.

In the appended Raagmala, Bhairav is given the first position in the ‘mala’ or list (ਪ੍ਰਥਮ ਰਾਗ ਭੈਰਉ ਵੈ ਕਰਹੀ ॥). However, in the Raag system of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, Bhairav is placed at the 24th position. According to Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, Siree Raag holds the first position and is described as the supreme Raag (ਰਾਗਾ ਵਿਚਿ ਸ੍ਰੀਰਾਗੁ ਹੈ ਜੇ ਸਚਿ ਧਰੇ ਪਿਆਰੁ ॥ – Ang 83), this is further supported by Bhai Gurdas Ji (ਰਾਗਨ ਮੈ ਸਿਰੀਰਾਗੁ ਪਾਰਸ ਪਖਾਨ ਹੈ ॥ – Vaar 42: Pauri 376).

This inconsistency has led many scholars to question the appended Raagmala’s alignment with the Raag system of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji. It is clear that to think the appended Raagmala is truly related to Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji and Bhairav is indeed the first and supreme Raag is clearly untrue as Siree Raag is the first and supreme Raag according to Gurbani and Bhai Gurdas Ji, the first appointed scribe of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji. The Raags used and the significance given to particular Raags differ between the appended Raagmala and the entire Gurbani contained in Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji.

Closely studying the Shabads, Ashtpadis, and Chhands in Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, we find a unique system for numbering stanzas. Each stanza or couplet is given a number when it ends, showing its position in the hymn and that it is complete in meaning. The Fifth Nanak, Guru Arjan Dev Ji, developed a hierarchical numbering system, where the total number of stanzas and hymns is clearly mentioned as totals and grand totals that run throughout. This system is so precise that it prevents anyone from adding or removing stanzas without disturbing the numbering, making it a foolproof way to preserve the integrity of Gurbani.

Now, let’s compare this to the numbering system in the appended Raagmala.

In the description of Bhairav Raag in the appended Raagmala, the numbering is inconsistent. For example:

ੴ ਸਤਿਗੁਰ ਪ੍ਰਸਾਦਿ ॥ ਰਾਗ ਮਾਲਾ ॥

ਰਾਗ ਏਕ ਸੰਗਿ ਪੰਚ ਬਰੰਗਨ ॥ ਸੰਗਿ ਅਲਾਪਹਿ ਆਠਉ ਨੰਦਨ ॥

ਪ੍ਰਥਮ ਰਾਗ ਭੈਰਉ ਵੈ ਕਰਹੀ ॥ ਪੰਚ ਰਾਗਨੀ ਸੰਗਿ ਉਚਰਹੀ ॥

ਪ੍ਰਥਮ ਭੈਰਵੀ ਬਿਲਾਵਲੀ ॥ ਪੁੰਨਿਆਕੀ ਗਾਵਹਿ ਬੰਗਲੀ ॥

ਪੁਨਿ ਅਸਲੇਖੀ ਕੀ ਭਈ ਬਾਰੀ ॥ ਏ ਭੈਰਉ ਕੀ ਪਾਚਉ ਨਾਰੀ ॥

ਪੰਚਮ ਹਰਖ ਦਿਸਾਖ ਸੁਨਾਵਹਿ ॥ ਬੰਗਾਲਮ ਮਧੁ ਮਾਧਵ ਗਾਵਹਿ ॥੧॥

ਲਲਤ ਬਿਲਾਵਲ ਗਾਵਹੀ ਅਪੁਨੀ ਅਪੁਨੀ ਭਾਂਤਿ ॥ ਅਸਟ ਪੁਤ੍ਰ ਭੈਰਵ ਕੇ ਗਾਵਹਿ ਗਾਇਨ ਪਾਤ੍ਰ ॥੧॥

Here, after eight lines of Chaupai, we see “॥੧॥” However, the last two lines don’t complete the family of Bhairav Raag. Lalit and Bilaaval are included in the next couplet (Dohra), which also ends with “॥੧॥”

This inconsistency in representing a complete family of a Raag is seen in other Raags too. The system in the appended Raagmala does not follow the organized and structured style used by the Incorruptible, Unchanging, and Perfect Guru in the Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji.

In the appended Raagmala, “॥੧॥” is used repeatedly, and at the end, it appears twice: “॥੧॥ ॥੧॥” Clearly, the style and numbering in the appended Raagmala differ from the system followed in the Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji.

Gurbani follows a distinct and unique system of grammar, which is also adhered to in Bhai Gurdas Ji’s Vaars. However, the appended Raagmala deviates from this system. For instance, in the line ਰਾਗ ਏਕ ਸੰਗਿ ਪੰਚ ਬਰੰਗਨ ॥, there is no Aunkar ( ੁ) under ਰਾਗ or ਏਕ to indicate whether they are singular or plural, implying that a single Raag has five wives and eight sons.

Such inconsistencies, including the use of Mukta and Sihaari in the appended Raagmala, do not align with the grammar of Gurbani. If the appended Raagmala were Gurbani, this would mean Guru Arjan Dev Ji and Bhai Gurdas Ji intentionally abandoned the established grammar of Gurbani for a different style in the appended Raagmala. Alternatively, it suggests that the appended Raagmala was not authored by Guru Arjan Dev Ji nor Bhai Gurdas Ji.

The ancient (puraatan) manuscripts of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji that included the appendix of Raagmala often contained other compositions in the appendix that appear after Mundaavani. In almost all cases where there is more than one appended composition present in the appendix, all other appended compositions appear before Raagmala:

All these seven compositions were unanimously discredited by the Panth. Over time, it was acknowledged that certain individuals had mischievously inserted these writings at the end of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji. However, these compositions held no legitimacy or standing when compared to Gurbani.

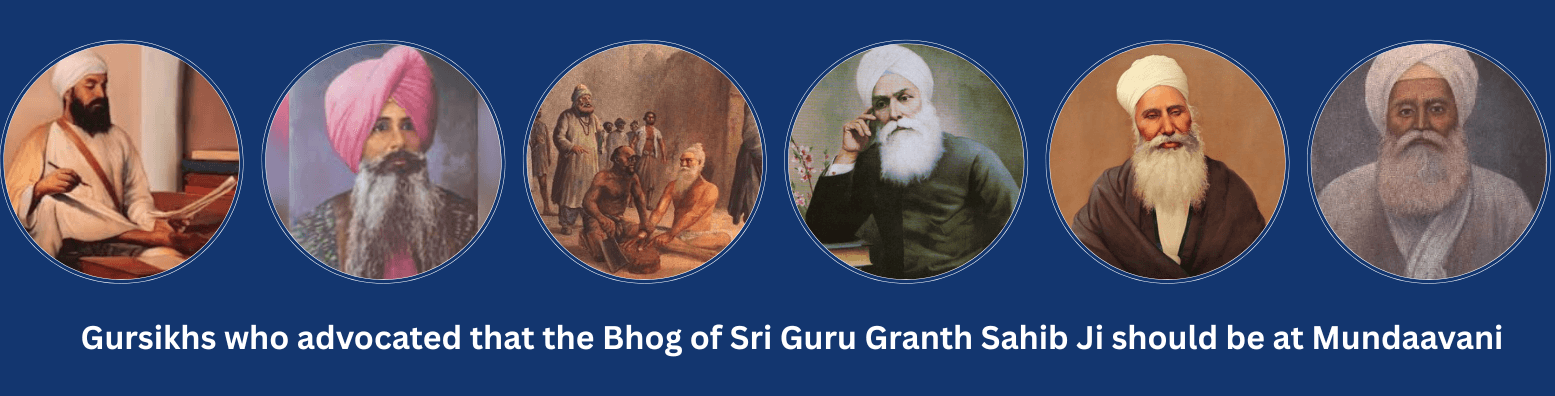

Many prominent Sikhs have been vocal that Raagmala should not be considered part of the main body of the holy text of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, nor be confused to be understood as Gurbani or be given the status of Gurbani, therefore making Raagmala’s inclusion and reading unnecessary and unimportant. Among them included:

Kavi Santokh Singh (Nirmala scholar) – Writer of Gur Prataap Suraj Prakash Granth.

Giani Gian Singh (Nirmala scholar) – Writer of Panth Parkash Granth.

Swami Harnam Das (Udasi scholar) – Writer of Puraatan Beerhaa Te Vichaar.

Giani Ditt Singh – A leading figure in the Singh Sabha Movement.

Professor Gurmukh Singh – A prominent educator and founder of the Singh Sabha Movement.

Sant Attar Singh Mastuana – A prominent Sikh saint and preacher.

Pandit Tara Singh Nirotam (Nirmala scholar) – A well-known Sikh scholar.

Pandit Kartar Singh Dakha (Nirmala scholar) – A prominent Sikh scholar.

Bhai Kahn Singh Nabha – Author of Mahan Kosh, a major work of Sikh lexicography.

Professor Sahib Singh – Known for his commentary on Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, Gurbani Darpan.

Dr. Ganda Singh – Renowned Sikh historian and researcher.

Professor Piara Singh Padam – Renowned Sikh historian and researcher.

Bhai Sahib Randhir Singh Narangwal – A notable Sikh saint who was a scholar and writer, known for his work on Sikh philosophy.

Shaheed Bhai Fauja Singh – A Sikh saint-martyr who laid down his life in the struggle for Sikh rights.

Shaheed Bhai Anokh Singh Babbar – A courageous Sikh saint-martyr, associated with the Babbar Khalsa movement.

These influential Sikh scholars and leaders advocated that the Bhog (completion) of a full scriptural reading should occur at Mundaavani, as it is the concluding passage of Gurbani in Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, rather than at the appended Raagmala.

The original Raagmala can be found in the poetic novel titled Maadav Nal Kaam Kandla, written by the poet Alam. One of the main characters in this story is Pandit Maadav Nal, an expert in Indian classical music. The narrative revolves around Pandit Maadav Nal and a lady named Kaam Kandala. In this ancient novel, Indian classical music is glorified, with references to various raags that align with the Hanuman Mat. Stanzas (34 – 38 of 179) from this novel have been used by scribes over time, particularly those passionate about expanding their knowledge of Indian music.

As a result, some scribes, particularly those with a deep interest in raags, included the Raagmala in the appendix of the Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji. Traditionally, space was left at the end of the Guru Granth Sahib for appendices, which were typically used for details like the process of making ink. However, some scribes also added items of personal significance, such as raags, to this section

According to Prof. Piara Singh Padham, Raagmala is a part of a love story written by the poet Alam in 1583 AD, based on Sanskrit/Prakrit sources. The story, titled Madhav Nal Katha, is in Hindi and consists of 353 stanzas. Prof. M.R. Mojumdar, a history lecturer at Baroda College, wrote to Mr. Padham that the story was popular in western India, particularly in Gujarat. The Hindi version, composed by the Muslim poet Alam, was written in 1583 AD, just a decade after Akbar’s conquest of Gujarat. It was commissioned by Raja Todar Mal, a Mughal cabinet minister, for the enjoyment of Emperor Akbar. Alam himself mentions in the foreword that the story was created for Akbar’s pleasure.

Some supporters of Raagmala claim that the poet Alam of 1708 AD copied Raagmala from Guru Granth Sahib. However, this claim is refuted in the Hindi Manuscript Report (1923–1925), which notes that Alam, author of Madhavnala Kama Kandala Nataka, wrote his work in 1583 AD during Akbar’s reign. This distinguishes him from another poet Alam, who wrote on erotic subjects during Bahadur Shah’s reign (1707-1719).

To justify the necessity and importance of Raagmala’s inclusion in the appendix Guru Granth Sahib Ji, and to even go further and elevate it to the status of divine revealed Gurbani, some propose that Guru Arjan Dev Ji followed a similar classical Raag system, as mentioned in Raagmala. However, this theory fails to explain why Raags such as Raag Malkaus, Raag Deepak, and Raag Megh, which are part of the six main Raags in Raagmala, do not appear in Guru Granth Sahib Ji. Furthermore, in Raagmala, each main Raag has five wives and eight sons, but none of the 31 Raags in Guru Granth Sahib Ji feature a female Raag (Raagni), further disproving the connection between the two.

Raagmala, appended to Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, is not a sacred or divine text but a worldly composition rooted in the secular poem “Madhav Nal Kaam Kandlaa” by poet Alam in 1583. It reflects the Hanuman school of Indian music, listing raags without spiritual intent. Unlike Gurbani, authored by the Gurus with divine inspiration, Raagmala lacks authorship attribution and devotional content, serving merely as a musical catalog.

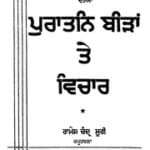

Below are images from Kaam Kandlaa book

Tap the image to enlarge it.

Do you agree that Sikhs who followed Gurbani during the time of Guru Nanak Dev Ji were saved? If yes, then the appendix composition of Raagmala did not exist during that period. So, for argument’s sake, if Sikhs were saved without the appended composition of Raagmala between the time of Guru Nanak Dev Ji and Guru Ramdas Ji, why would they not be saved by reading Gurbani from “Ik Oan-kaar” to “Tan Man Theevai Hariaa”?

Supporters of the appended Raagmala being considered Gurbani claim it was included in Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji during the time of Guru Arjan Dev Ji. However, to suggest that one cannot be saved without reading the appendix of Raagmala, and will instead go to hell, undermines the entire Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, from “Ik Oan-kaar” to “Tan Man Theevai Hariaa.“

Yes, it is important to read all of Gurbani. However, do you know that Guru Arjan Dev Ji sealed Gurbani at Mundaavani? This means that no Gurbani exists after Mundaavani, and wherever Raagmala is found in Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, it falls in the appendix, which is outside the seal of Mundaavani. Therefore, anything outside the beginning and end of Gurbani is not considered part of Gurbani.

There is a contents page called Tatkraa in Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji – do you read that? Guru Sahib also included numbers at the end of each stanza – do you read those? And the Ang numbers at the top of each page – do you read those?

Older handwritten copies of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, that were scribed by the decedents of the mischievous Prithi Chand, known as the Khaaree Beerh, that included the appendix of Raagmala, also had other compositions in the appendix, between the final seal Mundavani and the appended Raagmala, such as:

Do you read these compositions?

It is important to note that all seven of these compositions found in the appendix of some manuscripts of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, which were included after the seal of Mundaavani but before the appended Raagmala, were unanimously discredited by the Panth. It was acknowledged that these compositions were added by mischievous individuals over time, but they had no standing against Gurbani. This decision was accepted by all Sikhs, including supporters of the appended Raagmala.

Satguru Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji teaches us:

ਲੋਕ ਪਤੀਆਰੈ ਕਛੂ ਨ ਪਾਈਐ ॥

“By trying to please other people, nothing is accomplished.”

(Ang 736)

We have the choice of either reading a composition that was not authored by the Gurus and therefore is not Gurbani, simply to please others, or we can earn the blessings of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji by following the Hukam (command) found within Gurbani:

ਮੇਰੇ ਸਾਹਿਬਾ ਹਉ ਆਪੇ ਭਰਮਿ ਭੁਲਾਣੀ ॥ ਅਖਰ ਲਿਖੇ ਸੇਈ ਗਾਵਾ ਅਵਰ ਨ ਜਾਣਾ ਬਾਣੀ ॥

“O my Master, I was confused. From now on, I will sing only the text You have written and will never consider any other composition as Bani, the sacred Word.”

(Ang 1171)

Whether the minority or the majority don’t read the appended Raagmala makes no difference—the truth remains the truth.

For argument’s sake, if the entire Panth agrees that the appended Raagmala has the status and importance of Gurbani and begins reading it, will that solve the Panth’s problems? Evidence suggests that those who don’t read the appended Raagmala – individuals, groups, or organizations – show more unity and stability than those who zealously read it, even as part of their Nitnem, daily prayers.

If reading the appended Raagmala truly brings unity, then given that the majority of the Panth already reads and accepts it as Gurbani, why is the Panthic situation worsening, with increased external and internal attacks by anti-Sikh forces?

Is reading “Ik Oan-kaar” complete in itself? Is reading from “Ik Oan-kaar” to “Gur Prasaad” complete in itself? Is reading the entire Japji Sahib complete in itself? Every line of Gurbani is perfect and complete. To claim that reading Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji is incomplete without Raagmala suggests that all Gurbani from “Ik Oan-kaar” to “Tan Man Theevai Hariaa” is imperfect.

Does this imply that those who do Naam Abhiaas (meditation on the Divine Name) and Nitnem (daily prayers), but are illiterate and cannot read Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, are not saved? This undermines the power of the Gurmantar, the Divine Name of Vaheguru.

In 1936, the first edition of the Sikh Rehat Maryada was published by the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC), the official Sikh representative body of the time. Endorsed by the then Jathedar of the Akal Takhat, this document clarified that Gurbani concludes with the composition titled Mundaavani Mahalla 5, while also acknowledging the presence of appended compositions such as Raagmala in Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji. It stated:

“The complete reading of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji (Sadhaaran or Akhand) should be followed by the reading of ‘Mundaavani.’ (Note: There is a difference of opinion within the Panth regarding the inclusion of the appended ‘Raagmala’ in Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji and for this reason, it should not be removed from an existing handwritten or printed copy of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji.)”

Later, in 1945, provisions were introduced for Sikhs who wished to include the appended compositions during the full recitation of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji. The revised 1945 edition of the Sikh Rehat Maryada made it clear that no Sikh should be reprimanded or penalised for choosing to read the appended Raagmala when concluding a complete scriptural reading.

The amended Sikh Rehat Maryada (Article XI, a) states:

“The complete reading of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji (Sadhaaran or Akhand) should be followed by the reading of ‘Mundaavani.’ The appended ‘Raagmala’ may or may not be recited according to the local custom or according to the wishes of the person(s) who arranged the reading (Paath). (Note: There is a difference of opinion within the Panth regarding the inclusion of the appended ‘Raagmala’ in Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji and for this reason, it should not be removed from an existing handwritten or printed copy of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji.)”

Below are images of Puratan saroops of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji

Tap the image to enlarge it.

Throughout Sikh history, revered saints and scholars have addressed the topic of the appended Raagmala with humility and a commitment to Panthic unity. While views on its status have differed, none considered it a threat to the sanctity of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji or Sikh unity.

Sant Gurbachan Singh Ji Bhindranwale, the respected head of Damdami Taksal—a traditional seminary where teachings are passed down and followed with deep reverence rather than open enquiry—upheld the recitation of the appended Raagmala as Gurbani, in line with his institution’s tradition. Such seminaries often emphasize preserving the teachings of predecessors without question, which can lead to fixed views. Still, Sant Gurbachan Singh never condemned those who differed. He praised Bhai Sahib Randhir Singh Ji, founder of the Akhand Kirtani Jatha (AKJ), who did not accept Raagmala as Gurbani, as a respected saintly figure that he admired. Both respected Sikhs showed that such differences were minor and never grounds for division.

His successor, Sant Kartar Singh Bhindranwale, continued this spirit of inclusivity. He regularly attended Akhand Paaths at the home of Shaheed Baba Avtar Singh in Kurala, where Paaths were concluded at Mundaavani in line with Akhand Kirtani Jatha’s practice, without the reading of the appended Raagmala. He never objected. Likewise, members of Akhand Kirtani Jatha attending Paaths at Mehta Chowk—where the appended Raagmala was recited—remained respectful. These mutual gestures reflected shared reverence for the Guru over differences in practice.

In 1978, Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale called upon the members of Akhand Kirtani Jatha—despite their differing views on the appended Raagmala—to join Damdami Taksal in peacefully protesting the Nirankari cult’s sacrilege. Eleven members of the Akhand Kirtani JAtha and two from the Taksal were martyred following a bloody massacre committed by the Niirankari cult with the help of the Authorities on 13th April 1978. Sant Jarnail Singh personally led their funerals with full honours, clearly showing that he did not see differing views on the appended Raagmala as a basis for exclusion or judgment.

Though initially echoing his seminary’s view that not reading the appended Raagmala was Manmat, Sant Jarnail Singh revised his stance after being respectfully challenged by Bibi Harsharan Kaur of Akhand Kirtani Jatha. He apologised and never again criticised those who did not read the appended Raagmala. This openness was reflected in daily life—during his stay at Sri Darbar Sahib, Langar for him and his bibeki companions was prepared by Bibi Pritam Kaur, an Amritdhari whose roots were from the Akhand Kirtani Jatha who did not accept Raagmala as Gurbani. Rather than raise objections, Sant Jarnail Singh praised AKJ in his speeches. Despite his influence at Sri Akal Takhat Sahib in 1984, he never enforced the practices of his seminary, which included the recitation of the appended Raagmala.

In conclusion, the inclusion of Raagmala in the appendix to Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji does not compromise its integrity. The universally accepted Gurbani begins with Japji Sahib and ends with Mundaavani Mahalla 5, preserving the spiritual completeness of the Granth. The appended Raagmala, attributed to poet Alam, is of worldly origin and optional. Its recitation is a personal or local tradition, as affirmed by the Sikh Rehat Maryada.

Historically, manuscripts marked the end of Mundaavani with blank spaces or floral patterns, clearly distinguishing the core text from any appendices. However, in the modern standardised SGPC printed form of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, the appended Raagmala appears immediately after Mundaavani on the same Ang, rather than a new Ang. Thus, it has confused those unfamiliar with manuscript tradition and has led some to mistakenly view it as an integral part of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji. However, sadly, some individuals—whether misinformed or deliberately mischievous—have intentionally exaggerated the issue of the appended Raagmala in an effort to confuse and mislead naive Sikhs, and to undermine the Sikh faith from within. Yet, differences over this appendix have never compromised the unity of the Panth, nor do they diminish the complete spiritual authority of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji. The lives and actions of Sant Gurbachan Singh Ji, Sant Kartar Singh Ji, Sant Jarnail Singh Ji, Bhai Randhir Singh Ji, and countless other Gursikhs make it clear that this has never been a cause for division.

The Sikh Panth remains firmly united in its love and reverence for Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, and stands proud that its sacred scripture has remained intact, unchanged, and above corruption—unlike the altered texts of many established religions, which went unchallenged for centuries due to tightly controlled interpretation and suppression of dissent, often enforced by the threat of death for apostasy. Today, however, the authenticity of the scriptures belonging to what are considered the major established religions of the world is increasingly being questioned.

With the rise of the internet and greater access to previously hidden or suppressed information, this era allows open discussion and critical examination of texts that were once deemed the unquestionable Word of God. In contrast, more people are beginning to appreciate Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji—not only for its unmatched integrity and preservation, but also for its divine origin. Unlike the scriptures of other religions, which often rely on accounts of claims of private revelations said to be delivered through angels to individuals, later passed on and scribed by others, or composed by followers well after the founder’s time, Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji was revealed directly Guru Sahib who was the Divine personified in human form, and recorded, authenticated and given authority by them.

Outsiders exposed to the truth of Sikhi are increasingly recognizing not just the authenticity of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, but its Universal Truth—one that does not promote hatred, violence against non-believers, slavery, having intercourse with dead corpses, sexual exploitation, gender inequality, animal cruelty, or the glorification of base bodily desires through fantasies of bodily sensual rewards in the afterlife.

1. Divinely Authored and Authenticated by the Gurus Themselves:

Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji is the only religious scripture in existence directly written, compiled, and authenticated by the founders of its faith—the Sikh Gurus themselves. This divine process, initiated by Guru Nanak Dev Ji and completed under the guidance of Guru Gobind Singh Ji, ensures that every word is a direct revelation from God, untouched by external influences or later interpretations. Unlike other scriptures, which were often compiled long after their founders’ time, the Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji embodies the living voice of the Gurus, making it the ultimate and unadulterated expression of divine truth.

2. Infallible Numbering and Sound Weight System (Pingal):

Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji is safeguarded by a divinely inspired numbering system and the science of sound weight, known as the Pingal system. Each line of Gurbani is meticulously structured, with every word, letter, and vowel sound assigned a specific weight, creating a harmonic and mathematical precision that locks the scripture’s integrity. This system renders any attempt at alteration or tampering impossible, as even the slightest change would disrupt the divine balance of the text. No other scripture in the world employs such a sophisticated mechanism to preserve its purity, affirming Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji’s divine origin and unmatched authenticity.

3. Pristine Preservation Free from Human Corruption:

The direct involvement of the Sikh Gurus in the compilation of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji ensures its freedom from human interpolation or distortion. From its inception to its final form, the scripture was meticulously preserved under the Gurus’ divine guidance, with no reliance on later scribes or councils prone to error. This singular process of systematic preservation sets Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji apart as a scripture that remains exactly as God intended, a flawless and eternal guide for humanity.

4. Grammar (Vyakaran) as a Shield Against Adulteration:

Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji is composed in a unique grammatical system, divinely ordained, that serves as a built-in mechanism to detect any adulteration. This science of grammar (viaakaran) ensures that every verse adheres to a precise linguistic structure, making deviations immediately apparent. Such a divine safeguard is unparalleled in any other scripture, underscoring Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji’s authenticity as a text directly revealed by God, immune to human manipulation.

5. Uniformity Across Authorized Manuscripts:

Every authorized manuscript of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, as sanctioned by the Gurus, contains the same Gurbani, unchanged and consistent across time. This divine uniformity allows Sikhs to easily identify and reject any additions or alterations, such as the shabad attributed to Mira Bai, which the Sikh community unanimously recognizes as non-Gurbani. No other scripture maintains such absolute consistency across its original texts, proving that Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji remains exactly as it was revealed—a pure, divine revelation untouched by human hands.

1. A Scribe’s Betrayal Exposes the Quran’s Fragility:

Abdullāh ibn Saʿd ibn Abī Sarḥ, one of Muhammad’s trusted scribes tasked with writing down the Quran, abandoned Islam early on. Why? He claimed he could tweak the so-called divine revelations however he pleased, and Muhammad accepted these changes as God’s word. This isn’t just apostasy—it’s a glaring red flag. If Muhammad were truly a messenger of God, how could he fail to notice a human meddling with divine scripture? This suggests the Quran was never divinely guarded but was a product of human whim, vulnerable to manipulation from the start.

2. The Quran’s Messy Cover-Up Under Uthman:

Fast forward to around 650 CE, 18 years after Muhammad’s death. Caliph Uthman ibn Affan took drastic action to standardize the Quran, ordering all variant manuscripts burned to enforce a single version, the so-called Uthmanic codex. Why? Because there were different versions of the Quran, and this caused confusion among Muslims. If this book was truly the perfect word of God, why did it need a man to burn copies and fix it? This act looks like a cover-up, showing the Quran wasn’t perfectly protected but was a mess that needed human help to make it unified.

3. Muhammad’s Perverted Marriages: Aisha and Zaynab:

Muhammad’s personal life further dismantles any claim to divine character. At 54, he consummated his marriage to Aisha, a mere 9-year-old girl, a fact confirmed by Islamic sources. This isn’t just a cultural quirk; it’s the behavior of a pedophile, a man driven by lust, not holiness. Then there’s Zaynab bint Jahsh, his first cousin and the ex-wife of his adopted son Zayd ibn Harithah. Muhammad instructed Zayd to divorce her, then married her himself, with the Quran conveniently justifying it in Surah Al-Ahzab 33:37. This isn’t divine guidance; it’s a selfish act, using scripture to fulfill sexual desires. How can a man like this claim to speak for God?

4. An Illiterate “Prophet” Too Weak for His Role:

Islamic tradition boasts that Muhammad remained illiterate from birth to death, unable to read or write. Supporters call it a miracle, proof the Quran came from God. But consider this: if he were truly God’s chosen messenger, tasked with delivering a flawless message to humanity, why wasn’t he granted the basic tools—literacy—to do it properly? Instead, he relied on others to scribble his “revelations,” leaving them open to errors and tampering (see point 1). An all-powerful God would’ve equipped His prophet, not left him stumbling in ignorance. Muhammad’s illiteracy isn’t a virtue—it’s a crippling flaw that exposes his inadequacy.

5. A Sinful, Forgetful Fraud, Not a Holy Messenger:

Even the Quran admits Muhammad wasn’t perfect. Surah Muhammad 47:19 commands him to seek forgiveness for his sins, and other verses paint him as forgetful and flawed. A true prophet, chosen by an infallible God, should be a beacon of purity, not a bumbling sinner. These confessions strip away any pretense of divine favor, revealing a man all too human—petty, lustful, and unreliable. If the Quran itself admits his mistakes, why should anyone believe he was more than just a fake Prophet?

1. No Direct Authorship by Jesus Christ:

Unlike the Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, which was directly authored and authenticated by the Sikh Gurus, the Bible was not written or compiled by its central figure, Jesus Christ. Instead, it is a collection of texts penned by various human authors. The Old Testament predates Jesus by centuries, while the New Testament was written by his followers after his death. This lack of direct involvement from Jesus raises doubts about the Bible’s authenticity as a divine revelation tied to his teachings.

2. Delayed Writing of the Gospels:

The Gospels—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—form the core of the New Testament and recount Jesus’ life and teachings. However, they were composed 30-70 years after Jesus’ crucifixion. This significant time gap means they relied heavily on oral traditions rather than immediate, firsthand accounts from Jesus or his closest followers. Such a delay increases the risk of inaccuracies, embellishments, or alterations, undermining the reliability of these texts as authentic records.

3. Multiple Authors and Potential Inconsistencies:

The Bible is not a single, cohesive work but a compilation of writings by numerous authors spanning centuries. The Old Testament includes texts from ancient Hebrew prophets and scribes, while the New Testament comprises letters, narratives, and accounts from Jesus’ followers, such as Paul and the Gospel writers. This diversity of sources and perspectives introduces the possibility of contradictions and inconsistencies, weakening the Bible’s claim to a unified, authentic divine message.

4. Issues with Transmission and Translation:

The Bible’s journey through history involves extensive translations and revisions across languages, including Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek, Latin, and modern tongues. This process has led to documented discrepancies between ancient manuscripts, such as differences between the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Masoretic Text for the Old Testament, or between the Codex Sinaiticus and later New Testament copies. These variations suggest that the Bible, as we know it today, may not fully reflect its original form, casting doubt on its unaltered authenticity.

5. Lack of Original Manuscripts:

Unlike the Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji, which has preserved original manuscripts authenticated by the Sikh Gurus, the Bible lacks a single, definitive original text. What exists today are copies of copies, made years or centuries after the initial writings, with no direct authentication from Jesus himself. This absence of an original, authoritative manuscript further erodes confidence in the Bible’s integrity as a perfectly preserved divine scripture.

We’re here to help. Whether you’re curious about Gurbani, Sikh history, Rehat Maryada or anything else, ask freely. Your questions will be received with respect and answered with care.

Ask Question